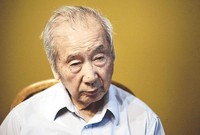

Frank M. KajikawaDeceased: July 11, 2011

Service Information: Memorial Visitation: Friday July 15th from 10am until

|

|

Obituary

Kajikawa,

Frank M. Kajikawa, 85 years, died July 11th

442nd Division WW II Army Veteran

Beloved husband of Mary.

Loving father of

Karen Kajikawa Lindblad, Lori Kajikawa and Christina (Alan) Peterson.

Devoted grandfather of Chuck, Jim and Julie

Dear uncle of many nieces and nephews

In lieu of flowers memorials to the

American Heart Association 3816 Paysphere Circle,

Chicago, Il. 60674 or www.heart.org appreciated.

Memorial visitation Friday July 15th from 10 am until memorial

service at 12 noon, both at Lakeview Funeral Home

1458 W Belmont Ave. Chicago, Il. 60657

Interment of ashes following at Montrose Cemetery

5400 N Pulaski Rd. Chicago, Il. 60630

FOR INFO. 773-472-6300 OR WWW.LAKEVIEWFUNERALHOME.COM

Messages

- July 15, 2011

-

FRANK M. KAJIKAWA

Nov. 21, 1925 – July 11, 2011

Frank M. Kajikawa was born near Tacoma, Washington, on Nov. 21, 1925. He was the youngest child (and the only son) of Sawaichi and Itoye Mitani Kajikawa. His sisters, Shizuko, Hiroko (Helen), Shiori (Shirley), Sue, and Midory all prededed him in death.

Frank’s mother died when he was a baby, and the family struggled to stay together during the Depression. In 1942, the family was relocated to the Minidoka internment camp near Twin Falls, Idaho. Frank was 15 at the time, and when he was of age, was drafted and served in the 442nd Infantry Regiment in Italy.

Upon his return from the war, he enrolled in college, then moved to Chicago, where he met and married Ayako Watanabe. They had two daughters: Karen and Lori. Aya passed away in 1973. Frank worked for the West Side VA Hospital until his retirement in 1994, but remained active in social and volunteer causes. Frank and Mary met in 1999 at the Levy Senior Center in Chicago and enjoyed similar activities and interests. They were married in 2003 and moved to Sun City in Huntley, IL in 2005.

In recent years, Frank was active in AARP and NARFE (National Active and Retired Federal Employees), and enjoyed his duties as President of Chapter 2181 for the past year, until his death. He also enjoyed traveling, walking, bingo, bowling, and his frequent visits to the library.

For many years, he spoke little of his wartime experiences. As time passed, he felt strongly that the story of the disregard of the civil rights of Japanese and Japanese-Americans during WWII needed to be told. He, with the assistance of Mary, developed a lecture on his experiences, first as a teenager interned in a barren Idaho internment camp, then as a soldier in Italy. He presented his lecture to local schools, libraries, AARP, NARFE, and other local cultural organizations, but particularly enjoyed sharing his experiences with junior high and high school students. He educated many people about the denial of civil rights of Japanese Americans citizens that are not adequately described in the history books. His wish was to make people aware that this would never happen again. - July 15, 2011

-

Recalling life in an American internment camp during WWII

By THAO NGUYEN, The (Crystal Lake) Northwest Herald

When Frank Kajikawa was 15, the official notices of removal appeared on the telephone poles in his town.

Kajikawa, an American-born citizen of Japanese heritage, lived with his parents and five sisters in a small farming community in the suburbs of Tacoma, Wash., an area with a significant Japanese-American community. His parents were first-generation Japanese immigrants who made their living working on a friend's farm.

"Like everybody else, they came here in hopes of finding a better life," Kajikawa, who lives in Huntley, Ill., said.

Now 84, Kajikawa was a high school freshman when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. While he and his family mourned the tragedy like other Americans, they also feared the repercussions that people of Japanese descent in the country would face, Kajikawa said.

Their fears were realized when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942. The order authorized the Secretary of War and U.S. armed forces commanders to declare military areas in which any or all persons they deemed necessary could be excluded. Many Germans and Italians also were held in camps under the Alien Enemy Act.

Although the order did not name a particular ethnic group, it largely was used to evacuate about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the Western Defense Command area, which included states near the Pacific Coast such as California, Oregon and Washington.

"They figured if we were traitors, we could help Japan by sabotaging ships on the West Coast," Kajikawa said.

After the removal notices went out, most people were given two weeks to pack up their belongings and report to an assembly center to await placement. Others who lived in places the government considered critical areas had only 48 hours. People who defied the order were thrown into jail.

Although he and his family could bring with them only what they could carry, Kajikawa said he knew of other people who were worse off. Shop owners with lucrative businesses had no choice but to abandon them. Because of time constraints, people who owned boats or other valuable property were forced to sell at rock-bottom prices.

"The Japanese living on the western coast suffered a great economic loss during this period," Kajikawa said.

Kajikawa and his family were sent to a camp in Idaho called Minidoka after weeks of anxiety and uncertainty about their situation. The camp consisted of 44 blocks of barracks that could hold about 10,000 people. Although families were allowed to live together, Kajikawa said, family unity suffered overall because children and adults did not often mingle during the day. The presence of guards also was a daily reality for the inhabitants.

"I was green behind the ears; I didn't know what was going on," Kajikawa said. "It wasn't until we arrived at the camp that I understood we were prisoners of war."

Kajikawa said that people in the camp for the most part did not try to resist their situation despite harboring resentment over being deprived of their civil rights as citizens.

"It was wartime; the government threw the Constitution out of the window," Kajikawa said. "The Japanese have a saying 'shikata ga nai.' It cannot be helped. I think people on the whole accepted what had happened to us. We were not exactly kicked around in there."

The atmosphere of hostility toward Japanese-Americans at the time was so pervasive that even newspapers and celebrities openly made derogatory comments about them, Kajikawa said.

"I knew that we were in a very dire predicament because we looked like the enemy, but we were not the enemy. We were American citizens, too," Kajikawa said.

After living in Minidoka for nearly a year and a half, Kajikawa headed off with one of his sisters to Salt Lake City, where he had a job lined up doing housework for a family while going back to high school.

The government previously had announced that people interned in the camps could relocate anywhere outside the Western Defense Command area as long as they could find a sponsor or work. The rest of Kajikawa's family ended up finding jobs with churches and hospitals in Peoria.

Kajikawa eventually was drafted into the U.S. Army and assigned to the 442nd Infantry Regiment, which was an Asian-American unit made up of mostly people of Japanese heritage. Although Kajikawa joined because he was sent a draft notice, other young Japanese Americans volunteered for service, causing a rift in family relationships.

"Some fathers threw their sons out of the house over it," Kajikawa said. "They said: You're fighting my country. How can you volunteer to join the American Army when they were the ones who put us in the camps?"

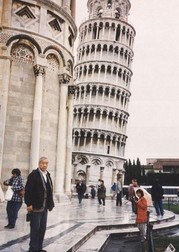

After two years in the Army in which he spent time guarding German prisoners in Italy, Kajikawa enrolled in college. He finally settled in the Chicago area near the rest of his family and worked in VA hospitals for nearly 31 years before retiring in 1994.

As he got older, Kajikawa said he begin to realize the need for his story to be told. Although there are volumes of books dedicated to World War II, Kajikawa said he felt that the history of Japanese internment camps was a rarely covered subject.

"This is a part of American history, and it should not be forgotten," Kajikawa said. "As long as I'm alive, it will be told. We need to let young people know that what happened to us should not have happened to anybody under our Constitution."

As part of his campaign to educate people about these internment camps, Kajikawa gives talks about his experiences growing up during the war and living in Minidoka. He already has presented his story at an AARP meeting but plans to ask the superintendent of the local school district and the director of the Huntley Area Public Library for permission to share his history with even more people.

"I may forgive my government for what it's done to me, but I will never forget," Kajikawa said. "I want to remind people that they should not let hysteria rule them. I hope that what's happened to us will never happen to anyone else."

In 1983 the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians issued its findings in "Personal Justice Denied," which concluded that the incarceration of Japanese-Americans had not been justified by military necessity. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush signed H.R. 2991 issuing a formal apology to the 82,000 living survivors of the internment camps. He also granted each one $20,000 in monetary redress and allocated additional money toward educating the public about the camps.

"I know they're embarrassed, but that should not stop them from telling our story," Kajikawa said. "They should be proud that they are trying to right a wrong."

442nd

Pisa

Revisits Pisa In Italy